The Abbey Theatre's launch 120 years ago

Willie Fay picked up a paintbrush. Annie Horniman designed costumes. That’s how it started.

From an abandoned book manuscript.

It is easy to like The Irishman, or so he thought, watching the play in the darkened wings of a large theatre. The moving limelight from the back of the auditorium scrapes the side of the stage, illuminating, for just a moment, the shy wiry man in his early twenties, unshaven and dressed in ragged shirt and trousers. It’s opening night in Manchester, and Willie Fay is far from Dublin.

The Irishman, a lively melodrama set during the Land War, is crammed with courageous and wicked thrills. An admirable young man from a British-ranking family breaks the law by helping desperate Irish tenants. A shocking scene depicts a landlord and his henchman knocking down a cottage with a battering ram. There’s an apologetically drunk hero showing up whenever he’s needed.

Now, Willie is waiting for the production’s final trick. The audience is looking into what appears to be an enormous mill onstage, built from two stories of towering wood. In an impressive feat of engineering, a gigantic mill wheel, powered by 2,000 gallons of real shimmering water stored in a tank below, begins to spin gracefully in the background. It’s a spectacle that’s sure to be as much a talking point as the play itself.

Inside the mill our hero is cruelly ambushed but inevitably turns the tables, throwing his attackers through a trap door into the drenching water below. Some may appreciate the irony; the bailiffs are the ones evicted from this landlord drama.

The Irishman is on tour in England, and Willie got a job with its technical crew because he built up the nerve to write a letter asking for it. The play’s author J.W. Whitbread approved of his experience touring with fit-up productions in Ireland and Scotland. Willie was quite happy to impress Whitbread, who, as manager of the Queen’s Theatre in Dublin, is probably the most powerful person in Irish theatre.

Working on a well-funded production reassures Willie, who wasn’t always confident in his choice of career. He had a comfortable upbringing in the south suburb of Rathmines in the 1870s and 80s, living in a Victorian redbrick house on Ormond Road. His father, a civil servant, hinted early on that a government job has its perks.

Willie was always close to his older brother Frank, who has a secretary job in a large accountancy firm, and often bought playscripts on his way home. His wardrobe in Ormond Road became a library, where Willie picked up plays by Beaumont and Fletcher, Ben Johnson and Christopher Marlowe. Equipped with Frank’s library, he began to stage productions with a group of friends, first in their living rooms and then in halls around Dublin.

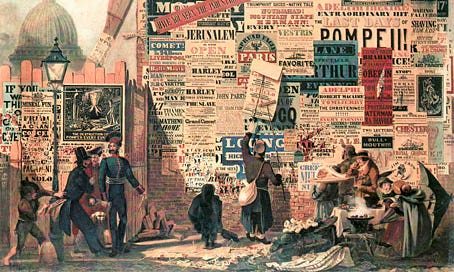

In these years after the industrial revolution, the hi-tech dazzle of the commercial theatre had set a standard for even an amateur production to have a spectacularly painted backcloth. So Willie borrowed a book on scene painting and began experimenting with a brush in the study room where he was supposed to be preparing for his civil service exam. The key to such stage design was learning how to paint in distemper - the mixing of glue with colours to create a quick-drying scene that, in dark colours, glows under limelight. On Willie’s first try, the paint soaked through the linen and destroyed the wall behind it. Frank helped him wallpaper the room before their father noticed.

Unsurprisingly, Willie failed his exam. He got a job in an office and started attending acting lessons until, at 19, he was asked to join a fit-up company touring the south of the country. The job involved rigging lights, transporting period costumes, and mounting romantic sets depicting nobles’ castles and picturesque lakes. “Very well. But you’ll not come back again,” said his father.

For the next six years, Willie toured with several companies besides Whitbread’s production of The Irishman. He regularly practised the finer details of scene painting, focusing on the craggy edges of a gloomy cave, or the elegantly curved hills and trees of a pleasant countryside. For one supernatural drama, he suspended a pane of frosted glass across the stage to make the ghost mysteriously opaque.

In between tours, he stayed in his own lodging in Dublin, and got paid working with a chief engineer in Dublin Corporation. With changes in technology, the city was undergoing a large-scale changeover from gas-fuelled power to electricity.

It’s sometime in 1897 when Willie is home from touring, and his brother invites him to his lodging in the Liberties area in Central Dublin. Soon after Willie arrives, Frank tells him about the new recitation and projection classes he’s teaching in town, based on his research of Italian opera. They have a long conversation about their parents, whether or not Home Rule will happen without Parnell, and the theatre industry in Dublin - much of which Frank is not a fan of.

Frank tells Willie the Théâtre Libre has closed its doors. They often wondered about this little theatre, the most exciting in Paris, competing against the city’s flashy commercial theatres with its painstaking productions of European drama. But the closure of Théâtre Libre wasn’t something to mourn. Its founder André Antoine, who, like Frank, was a clerk by day and went to the theatre at night, has been asked to bring his darkly realist productions to larger stages. That gave Frank hope for him, his brother, but also for Irish theatre.

“Willie, stay in Dublin and make theatre with me.”

“Standby, please.” says Willie, taking hold of what appears to be four rocking chairs bolted together to resemble a chariot, seating an actor dressed as Queen Maeve. There’s barely room backstage in the Antient Concert Rooms, where more than one hundred performers are involved in the biggest production this night in Dublin.

A stylish woman wades through the backstage crowd to help him carry the chariot. Maud Gonne, the activist, is the producer of tonight’s production, having organised it for the players of the women’s nationalist organisation Inghinidhe na hÉireann. Taking hold of the chariot on the opposite side is Alice Milligan - the Omagh-born playwright, director and designer - whose youthful face relaxes into a knowing smile. The play is going gloriously.

As stage manager of a sprawling production, Willie only manages a beleaguered expression through his new spectacles. It’s been four years since he told Frank he’ll stay in Dublin. For most of that time he’s been working steadily as an electrician. This is his first large-scale production in a while.

He manages to spot Frank in the stalls, scribbling happily into a notebook. A while back The United Irishman, a new nationalist newspaper, invited Frank to become their theatre critic. Ever since, he’s been admonishing the very Dublin theatre scene Willie worked hard to build relationships with. When Whitbread’s The Irishman came back to the Queen’s Theatre, Frank ran out of patience with its benign depiction of the colonial conflict. “A crude piece of unconvincing conventionalism, without any right to its name” he wrote, deciding the melodrama was out of tune with contemporary times.

In the Antient Concert Rooms, there is a sense that Milligan is a playwright of the moment, even if her script has no words. Her play is based on the classical form of tableaux vivants, in which performers move silently into frozen pictures to create historical events or famous paintings. Instead, Milligan’s production takes inspiration from heroic sagas of Irish mythology. Grania Mhaol confronts Queen Elizabeth. Sarah Curran and Anne Devlin assist Robert Emmet. The Children of Lir take flight.

Willie has seen a lot of flamboyant historical costuming in this time but he has never seen anything like Milligan’s imagining of Celtic dress. The long flowing robes sewed with bright spiral and zoomorphic embellishments, dressed with penannular brooches, make the characters appear warrior-like and druidic.

He has seen signs of this new Arts and Crafts movement before, at markets where craftspeople sold decorative clothes and metalwork dressed with medieval Irish details like spirals, peltas and triskeles. He had never seen it as the inspiration for theatre costuming.

So ecstatic was the response to Milligan’s production, there were shouts of “Aris! Aris!” from the stalls. Gonne, an astute producer, quickly organised another collaboration.

Four months later, Willie found himself directing a new production for Inghinidhe na hÉireann: a double bill of Milligan’s plays The Deliverance of Red Hugh and The Harp that Once Was. In the audience, a tall man in his thirties, dressed in a black suit and cravat, leaned forward in his seat, admiring the crystal-cut intonation of the Irish voices. Years later, William Butler Yeats recalled: “I came away with my head on fire”.

Willie and Frank were curious about Yeats and the other literati who made up the new theatre company: the Irish Literary Theatre. Yeats, best known for his romantic poetry collection The Wanderings of Oisin, caused a stir two years ago when his play The Countess Cathleen was accused of blasphemy. The Irish Literary Theatre may have produced plays by Irish playwrights but they nearly always hired English directors and actors. Frank asked in the United Irishman why they “cannot entrust the performance of their plays dealing with Irish subjects to a company of Irish actors”?

Most striking about the Irish Literary Theatre was that, in its self-esteem, it published a manifesto promising to transform Irish theatre. “It will show that Ireland is not the home of buffoonery and of easy sentiment,” wrote Yeats and his colleagues, passing stinging comment to Whitbread and the other melodrama-writers dominating the industry. Willie and Frank both read about how the Norwegian national theatre revolutionised theatre in that country. Could they be looking at the elements for the making of an Irish national theatre?

In surprising agreement with Frank’s criticism, Yeats and company approached Willie to direct an Irish cast in a new play - Casadh an tSúgáin by Douglas Hyde - at the Gaiety Theatre. Even so, the production could not save the Irish Literary Theatre from the internal conflicts that forced it to close shop. But Yeats was still determined to collaborate with the Fays.

Acutely, when Yeats learnt that Inghinidhe na hÉireann’s new production was going to be the myth play Deirdre by George Russell, he anticipated it would run short on duration. To make up the running time, he contacted them to suggest they also produce his new play Cathleen Ní Houlihan. This explicitly nationalist drama appealed immensely to the Inghinidhne’s audiences. (Years later, Willie might have guessed that chunks of Cathleen Ní Houlihan were ghostwritten by someone else).

For Cathleen Ní Houlihan, Willie designed a modest cottage set, muted in colour, with painted details suggesting a hearth, wall panels and framework. He thought it was important that the expected vibrant backcloth, depicting a copse of trees, be only glimpsed through the door and windows. Anyone other than Willie would probably try to turn the set into a spectacle, like the two-storey mill in The Irishman. He knew that for a more serious drama, restrained design can focus attention on the actors’ performances.

Afterwards, during jovial celebrations of Inghinidhe na hÉireann’s beloved production, Willie took a drag on his cigar. He watched as drinks were poured and passed between Frank and Maud Gonne, from his friends in the Ormond Road players to the actors and technicians in Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and one glass passed to the top of the room to Yeats. Past and present are colliding, and now the future seems open. Someone makes the serious proposal they all form a company.